Formulas are for Mules, Part II

Wait! Did you read Part 1 of this series? Click here to read now.

Before we start addressing the actual individual packages of nonsense formulas below, I wanted to expand a little on my main claim in Formulas are for Mules, Part I.

But first, a quick reorientation: You are not a mule. In other words, you are not a workhorse to be used for measuring the efficacy of your teachers. You are not an animal who needs no high-level understanding of the (mathematics) farm. If the metaphor is lost on you, go read Part I and come on right back. After all, we’re about to invoke yet another useful metaphor.

Yet another useful metaphor

You are not a computer. Computers have a real black-and-white, on-and-off, ones-and-zeroes way of remembering things. Computers also love storing symbolic placeholders (variables like x1 and x2) for input values that don’t come until much later (numbers like 3 and 4). You can code a formula—a function, to be more precise—into a computer program, and that program will save that formula for as long as you need. Whenever you feed the program some “inputs,” it will near-instantaneously pump out the appropriate “outputs” based on the stored operations in the program’s “formula.”

Gross.

What’s that, you say?

Gross!

Yeah, I agree; that’s the point! I’m not a computer either.

The problem is that I used to be taught in school as if I were both a mule (a teacher-measuring workhorse) and a computer (a soulless input-output machine with a perfect memory).

What’s even worse? I believed it—hook, line, and sinker.

My long-term memory and working memory are both pretty darn good—not that I know how they work, but that’s an article for another day. Like most things about my physical body, however, I expect that my memory will soon start to degrade, especially now that I have young children with budding memories of their own.

But back in high school, I was definitely a kid who could remember formulas for long enough to think that it was a useful endeavor. That said, I also had moments when I forgot them—usually after an extended period of time with no use of the formula or while under the pressure of time constraints… you know, like on TEST DAYS.

There’s nothing like a test day to screw with your amygdala, the brain’s center for the detection of and response to fear and stress. In fact, the one thing we do have in common with mules is the innate fight or flight response—that is, our shared coping mechanism for handling external stressors.

If you stress out a mule in the field, he’ll likely kick or back away. If you stress out a high schooler on test day, she’ll likely misremember a formula or, more likely, not be able to conjure it up at all, resulting in a psychological state equivalent to that of a toddler rocking in the fetal position—even if just for a moment while doing #36.

Even if you think you remember a formula—as every new student I meet thinks until proven otherwise—the stress of test day can easily contribute to the jumbling of all those memorized hieroglyphics.

Get to the point, rambler

The first three formulas I’d like to destroy mock scrutinize are probably the worst ones. What’s even worse is that they are taught in such close proximity to one another that I’ve very rarely met a high school junior who does not mix them up at least a little bit when first trying to recall them.

They are the Distance Formula, the Midpoint Formula, and the Slope Formula. I must apologize, of course, for repeating the F-word three times in that last sentence.

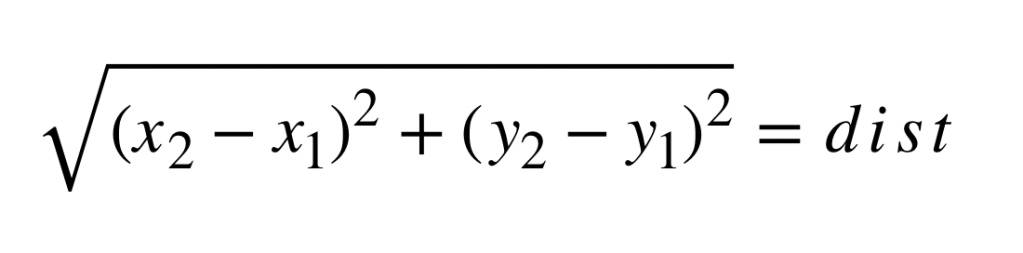

The Distance Formula

Let me be blunt here: you never needed to be taught the Distance Formula. Don’t get me wrong: I’m not saying you never needed to learn the formula. Rather, I’m suggesting that no teacher ever needed to stand up in front of your classroom and teach you this particular formula.

Now, you may find yourself thinking, Mark, if I didn’t need to be taught that formula, why did I still need to learn it, and how could I learn that formula without having been taught it?

You are following correctly, and you are rightly frustrated; however, my point is not that you needed to learn the formula when you were taught it. Instead, my point is that you had already learned the Distance Formula—most likely two years before you were even taught it!

By now, you may be justifiably filled with a righteous indignation: Mark, now you’re not even making sense. I couldn’t learn a formula before I was ever even taught the formula!

But you’re wrong, and I’ll prove it.

The Distance Formula isn’t real. It’s a sham. A farce. A pretense. A facade. I actually posit that it was invented to destroy your elegant understanding of something much simpler: right triangles.

Say what, now?

Mark, that’s just the formula again!

Alright, I’ll make it a bit clearer.

Wait just a second now…

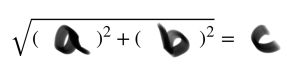

That’s right. The Distance Formula is simply a (much) worse way of notating that other thing:

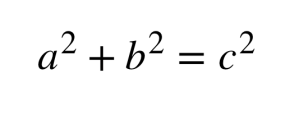

And that thing is simply a rearranging of that one thing that’s been written on your heart for years now:

If you haven’t figured it out yet, I’ll utter the simple truth: the Distance Formula is simply The Pythagorean Theorem.

And here is the same truth, stated slightly differently and without invoking the name of an ancient cult leader who wasn’t even the first schmuck to discover that truth: the distance between any two points on a plane can be conceptualized as the hypotenuse of a right triangle.

A pathetic state of affairs

For over the last decade, I have met privately or taught in small groups thousands of high school Sophomores, Juniors, and Seniors. Every time I meet a new student or start a new class, I start with the simple truth outlined above. In those more than ten years, I can count on two hands the number of students who already understood this elegant reality. I remember all eight of their faces, and with one of them, I even sought out the teacher who shared it so I could commend him for doing so.

Let’s take a darker turn

So you recognized the Pythagorean Theorem, eh? Good for you. But what is it?

What do you mean, Mark? I said I recognized it, and, thus, I know what it is!

No, I don’t want to know that the thing works; I want to know why or how the thing works.

Sorry, Mark; as my Geometry teacher taught me, I should just mention Pythagoras’s name in my prayers at night, and then I can trust that the thing will just work its ancient magic whenever I need it.

Now if that sounds like an exaggeration, just check out how the Pythagorean cult prayed to the number ten:

A prayer of the Pythagoreans shows the importance of the Tetractys (sometimes called the “Mystic Tetrad”), as the prayer was addressed to it.

Bless us, divine number, thou who generated gods and men! O holy, holy Tetractys, thou that containest the root and source of the eternally flowing creation! For the divine number begins with the profound, pure unity until it comes to the holy four; then it begets the mother of all, the all-comprising, all-bounding, the first-born, the never-swerving, the never-tiring holy ten, the keyholder of all.

Dantzig, Tobias ([1930], 2005) Number. The Language of Science. p. 42

I won’t settle to toe the line of the Common Core curriculum paradigm (the Geometry teacher’s instruction above); in fact, I’d actually like to push for an indefinite moratorium on the withholding of elegant mathematical truths from young people.

Mark, are you going to show us the thing or not?

Yes, of course I’ll show you the thing.

A square plus another square… equals a bigger square.

More specifically, the two-dimensional area, in square units, of a certain square can be added to the two-dimensional area, in square units, of another square to find the two-dimensional area, in square units, of a third, always-larger square.

When you blow a young person’s mind with elegant simplicity, you restore the power they forgot they had—the power that was stripped away from them when they were taught something seemingly complex.

Mark Hastings

I can only count on one hand the number of Sophomores, Juniors, and Seniors I’ve met who already knew that truth about the Pythagorean Theorem I’ve displayed above.

Please note that I do not blame them. I blame the Pythagorean cult system we call school (see my first post ever, You work too hard).

Why is this so important to me?

Well, when you blow a young person’s mind with elegant simplicity, you restore the power they forgot they had—the power that was stripped away from them when they were taught something seemingly complex.

Using yarn and Skittles, I’ve taught a classroom full of nine-year-olds “The Square Thing” (I spared them from the word theorem).

Yet, as a nation, we save this gem for eighth graders; we don’t explain what it means; and we name it after a very conspicuous ancient cult leader whose only goal in life was to keep the maths away from the masses.

Oh, right, and then we teach it to them again when they’re 15, under a totally different moniker (the Distance Formula) and in a totally different shape—without telling them that it’s just a fancier version of the other thing (Pythagorean Theorem).

The Midpoint Formula

Now that you get the name of my game, I’ll cut to the chase a little quicker on this one. What a stupid formula—in fact, it’s the only elementary formula with parentheses and a comma. Elementary indeed, my dear Watson. In fact, you were definitely taught the elegant simplicity underneath the ghastly shape of this formula while you were still in elementary school.

No, Mark! I didn’t learn that formula until Geometry class!

Indeed, you didn’t. But somewhere between third and sixth grade, you were definitely taught how to find the exact halfway point between any two numbers: average them (find the arithmetic mean, if you will).

Take this example:

Tommy and Sally each have some Skittles. Tommy has 13 Skittles. Sally has 27 Skittles. If Tommy and Sally love each other so much as to share their Skittles equally, how many Skittles would Tommy and Sally each get?

13 + 27 = 40

40 ÷ 2 = 20

(13+27)/2 = 20 Skittles.

So indeed, the midpoint “formula” is also no formula after all. It’s just a disgusting way to notate the following: “Average the X’s, and average the Y’s.”

Stop memorizing formulas. Seek the simple. Strive for elegance.

The Slope Formula

As I mentioned above, I always start cracking open a student’s conception of math, math class, formulas, etc by discussing (and replacing, perhaps restoring, or even revitalizing) the Distance Formula Pythagorean Theorem Square Theorem.

But before I share that good news, I always ask if they can recite the Distance Formula for me first.

Nine times out of ten, if the student can recall anything about it, they’ll mumble something along the lines of, “Oh yeah, maybe it’s like x1 + x2 in there or something”—at which point they’re mixing in elements of the Midpoint Formula—”or, no, wait, I got this; maybe it’s like x1 + x2 over y1 + y2…”—at which point they’ve confused the Midpoint and Slope Formulas… all just to try to recall the Distance Formula.

So what’s so wrong with that Slope Formula, you ask, since it’s true and all? In my opinion, it’s the linchpin for making sure everyone forgets all three of them!

You see, in direct contrast to the statistics I mentioned earlier, I actually can’t count the number of students I’ve met who already know “Rise over Run” because every student I’ve ever met already knows “Rise over Run”—they have it written on their heart along with the Pythagorean theorem and Averaging.

However, when we introduce the formulas, all that stored elegant simplicity gets disrupted, confounded, and intimidated into submission until a perfectly intelligent young person utters those dreaded words… “I’m just not good at math.”

How do we fix it? Like always, bring it back to basics. I don’t like the Slope Formula above because it doesn’t take into consideration that you can subtract in a different direction:

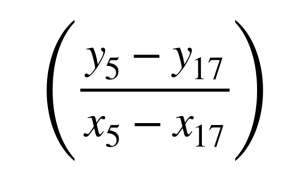

Or that you can subtract nonconsecutive, yet corresponding ordered pairs:

But mostly the problem is back to mules and computers—neither of which describes you. The tedious notation scheme above can be abundantly simplified in two ways.

The first:

And the second:

Oh, right, it’s just too good to be true! We’ve gone full circle, back to that which is written on your heart.

Well, we’ll actually save Circles for next time. Come back for Part 3.

This information just blew your mind, didn’t it?

In the next post, Mark is talking circles. Click here to read part 3 now! Please share this post with someone else who may find it useful!