A History of Revisions to the SAT, Part 1: The 1800s through the 1950s

Josh, why are you writing about a topic that every other person on this planet will find horribly boring?

Because I’m the only person who matters.

And because the history of standardized tests is fascinating. I mean, how did we wind up in a world where the course of students’ futures is determined by bubbles on an answer document?

More importantly, however, I’m writing about the history of the SAT format in order to use this history as a lens with which to view the changes to happening to the test in 2023-2024.

Most importantly, somebody decided it was a good thing to give me the ability to publish any writings on this blog that I wish…as long as they are related to tests or test prep. So the joke’s on you, Poindexter. If you don’t like it, you can get your own blog.

In this brief-ish history, I’ll be focusing on the changes to the test itself as well as the explicitly stated reasons for those changes. Many of the changes also have a goal of reducing biases in the test, but I’ll save that discussion for the book I’ll be begged to write after this post goes viral.

Hello, publishers.

I know you’ve been searching high and low for a thousand-page, impenetrable tome about the history of high-stakes college entrance exams. Ideally, this book would be written by some jerk who’s been convinced by the polite laughter of those forced to listen to his jokes that he’s a real comedian. Look no further. I’m your Huckleberry.

I’ll use this first part to focus on the beginnings of the test through the first really “standardized” versions. The second part will cover the first national panic over SAT test prep and score declines while the test itself remained fairly stagnant. The third part will discuss the whiplash of test format changes we’ve seen from the mid-‘90s to today.

A Short Tangent on Pre-SAT College Entrance Exams

In the 19th century, each American college gave a separate entrance exam. In 1890, Harvard President Charles William Eliot had the thought that a single, common test would be a good idea.1 As we now know, he was horribly wrong.

An Apology from the author: I’m deeply sorry to the single living person who loves the ACT and SAT. The “joke” with which I ended the previous paragraph was tone-deaf, insensitive, and unfunny. To show that I have learned my lesson, I will be donating $80-100 to two nonprofits—ACT, Inc. and the College Board—in the form of test fees the next time I sit for their respective tests.

In the early days of the 20th century, the College Entrance Examination Board was founded, and the first common college entrance exams were administered.

When the U.S. entered “The Great War” in the 1910s, the Army experimented with using multiple-choice tests to assign jobs to the massive influx of draftees. After the war, some idiot thought, “Hey, why don’t we take those Army tests, change them to high-stakes nightmares, and use them torture high school students around the country?”

Admittedly, I might have paraphrased that last part, but that’s the gist of it. Let’s stop living in the past and start living in the future: 1926.

Part 1: From Humble Beginnings

The 1920s

The SAT, which stood for Scholastic Aptitude Test, was first administered in 1926. The test consisted of nine subtests: seven Verbal—Definitions, Classification, Artificial Language,2 Antonyms, Analogies, Logical Inference, and Paragraph Reading—and two Math—Number Series and Arithmetical Problems. All together, the test included 315 questions and had a time limit of 97 minutes. According to Lawrence, et al (1998),3 “as late as 1943, students were told that they should not expect to finish” the test (p. 1).

In a report about the first SAT administration, the College Entrance Examination Board (which hadn’t yet been told by Sean Parker to drop the “Entrance Examination” from its name) stated that students were given practice booklets, which they were expected to complete ahead of time. Students who had not completed their booklets—and, thus, had not adequately prepared for the test—did not have their tests scored “because the scores obtained by candidates who had not studied the practice booklet could not be compared with the scores of candidates who had had ample opportunity to practice on the material of the examination” (1926).4

From the very beginning, the test makers acknowledged that test prep was necessary to get an accurate reflection of students’ abilities. Confusingly, the College Board tried constantly over the next century to make the test “uncoachable.” I know you’re utterly shocked to learn about the duplicity of the often profitable non-profit College Board.

The 1930s

In the early years of the test, the SAT was only administered once a year,5 and scores could only be compared within that year’s cohort of students. Starting in 1930, the SAT was split into Verbal and Math sections for the first time. The Verbal section consisted solely of Antonyms, Sentence Completion, and Paragraph Reading questions, but it would continue to see minor additions and subtractions over the next fifteen years.

Oddly, from 1928-1929 and 1936-1941, the test had no Math questions. Why did they split the test into two sections and then eliminate one of the sections? Your guess is as good as mine.

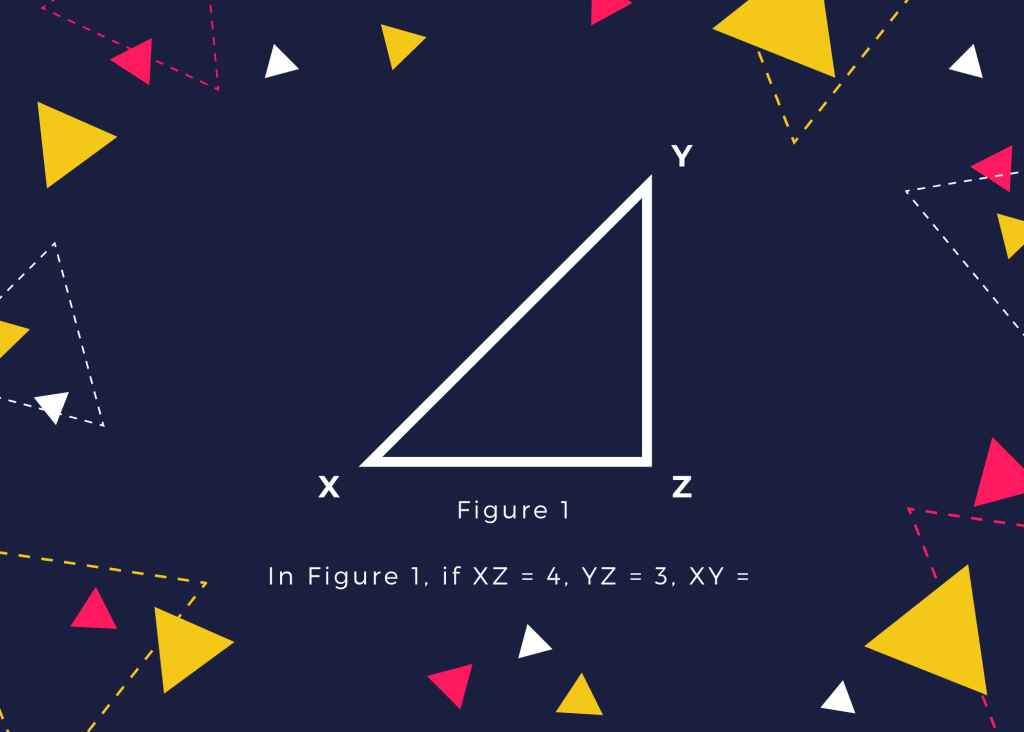

Check out this question, which is similar to one on the 1934 test:

Wild, right? To get the answer, you have to assume that angle Z is a right angle and then use the Pythagorean theorem your knowledge of the SAT’s love of 3-4-5 right triangles to find the answer of 5; otherwise, the problem is unsolvable. The modern test is full of qualifiers and wordiness. The modern language serves two purposes: first, it slows students down and confuses them; second, it provides cover from lawsuits over unfair questions.

At this time, the fee to take the SAT was $ 15, which is closer to $ 230 in 2022 dollars. With one yearly test administration, the College Board could price gouge use the law of supply and demand to appropriately price their test.

By 1938, enough additional schools had signed on to use the SAT as part of their admissions process that it started to become a de facto national test.

The 1940s & 50s

Demand from students increased to the point that the College Board began administering the SAT multiple times per year.5 Once the same students started taking the test multiple times, it became a bit inconvenient that they could not compare their scores to see if they had done better the second time around.

Noted non-profit the College Board would hate to miss out on a chance to charge students multiple times over something as silly as test scores, so, in 1942, they changed that. That year, using data from the 1941-1942 school year tests, the College Board created a reference group so that, for the first time, the SAT was standardized. This allowed scores to be compared across test dates.6

If you scored a 1000 (the expected average based on that 1941 reference group7) one year, and your friend scored a 1010 the next, you were finally allowed to internalize the shame of being the “dumb” friend. It’s a totally healthy attitude to have, but it would be easy to get rid of if someone simply yells at you not to feel that way.

The ’41-’42 reference group would continue to be used to scale SAT scores until 1994. Nothing about our world, country, students, or education system changed in those 50+ years, so this was a great call by the College Board.

The test content continued to change during the ’40s and ’50s as well.. During these years, the “classic” SAT took shape.

The Verbal section now consisted of familiarly unfamiliar Reading Comprehension, Analogies, Antonyms, and Sentence Completion questions.

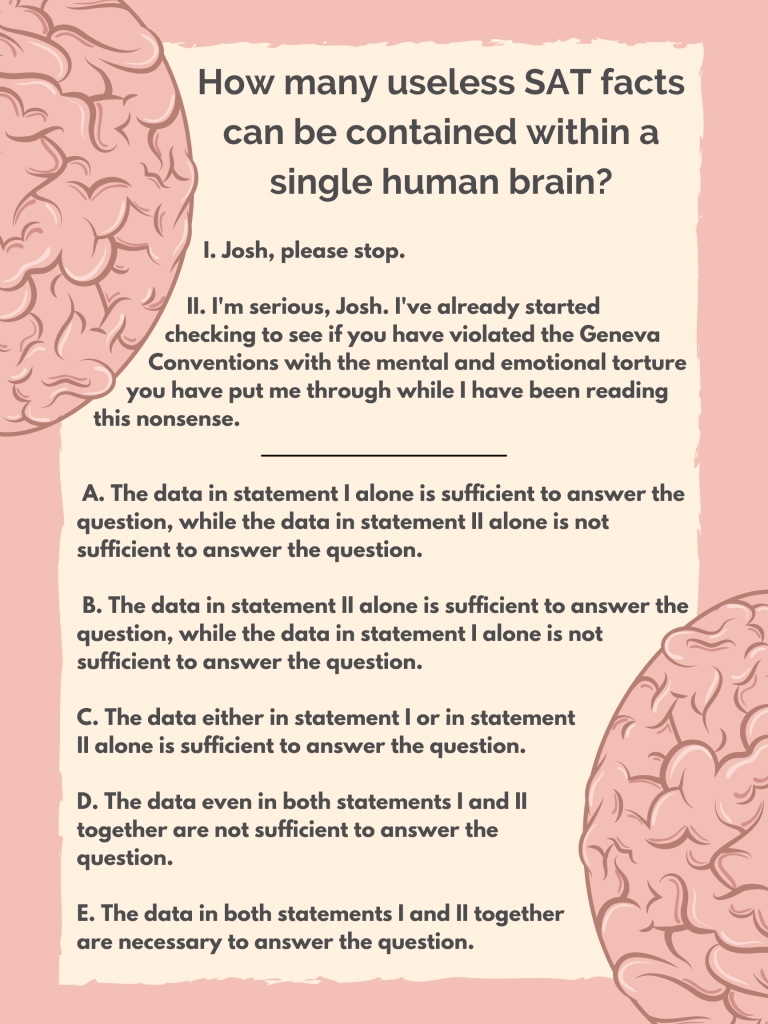

On the Math section, all questions were “upgraded” to include five answer choices, and, in 1959, Data Sufficiency questions arrived. These questions presented students with two statements, asking them which statement (or both or neither) was sufficient to answer a question related to the statements.

Summary of Part 1 and Teaser for Part 2

[Editor’s Note: Josh, change this to something more exciting. No one will want to read a section with such a straightforward heading. Also, remember to delete this editor’s note once the change has been made, you idiot.]

The first thirty years of the SAT were a time of great change to the format, administration, and scoring systems of the test. The test—conceived as a way to eliminate separate, college-specific entrance exams—served its purpose and gained steam.

Early twentieth-century educators were excited about the possibilities of standardized tests because these tests were cutting edge stuff. We could finally quantify the qualitative and reduce our children down to numbers. No longer were you forced to think of little Jimmy as the summation of his experiences, actions, thoughts, and feelings. Now, you only had to remember 1080. Way to go, 1080—I mean, “Jimmy.”

Part 2 will discuss the next thirty or so years of the test, including calls for the SAT to change and the College Board’s resistance to such changes.

1 See National Education Association (2020, June 25).

2 The Artificial Language subtest is just what is sounds like. Students were given vocabulary words and grammar rules for a made-up language, and they were then expected to translate basic English sentences into the artificial language and vice versa. Wild.

3 This report on the content of the earliest versions of the test was incredibly helpful and I can’t recommend it enough for losers like myself.

4 See College Entrance Examination Board (1926), page 1, for more information about the testing conditions and requirements of the first administration of the SAT.

5 See Dorans (2002), page 2, for more information about early SAT reference groups and scoring scales.

6 Again, Dorans (2002), page 2.

7 Dorans (2002), page 1.

Works Cited & Referenced

College Entrance Examination Board (1926). Annual Report of the Commission on Scholastic Aptitude Tests. College Entrance Examination Board.

Dorans, N. J. (2002). The recentering of SAT®scales and its effects on score distributions and score interpretations. ETS Research Report Series, 2002(1), i-21. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2333-8504.2002.tb01871.x

Lawrence, I.M., Rigol, G.W., Essen, T.V. and Jackson, C.A. (2003), A Historical Perspective on the Content of the SAT. ETS Research Report Series, 2003: i-19. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2333-8504.2003.tb01902.x

National Education Association (2020, June 25). History of standardized testing in the United States. NEA. Retrieved October 21, 2022, from https://www.nea.org/professional-excellence/student-engagement/tools-tips/history-standardized-testing-united-states

Wondering what changes came next? Surely things that will help students, lets find out.

Click here to read Part 2 where Josh will discuss changes made from 1960-1993. Please share this post with someone who may find it useful!